It was early Sunday morning. I grabbed some raisin bread and a banana and sat down in front of the television. Nothing prepares me for church like listening to people bicker about politics. But instead of meeting the press, I stumbled upon a piece on CBS that sent me down memory lane to old warehouses and hotel conference rooms, digging through dingy cardboard boxes, looking for loot to add to the oversized green plastic box I stored my treasures in until I grew old enough to realize how silly it looked to carry with me.

Some were colorful and metallic, others clean and crisp. Some were cut with the precision of a laser, others embossed, others glossed. There were the Diamond Kings and the diamonds in the rough, but it took mining the entire field to find all of the gems. And if you were lucky, you’d find the one that came with a stick of chewing gum.

Vodpod videos no longer available.I spent my childhood collecting baseball cards. My friends and I would go to card shows and local shops to buy packs of Topps, Fleer, and Donruss for a couple of dollars apiece [you could buy the packs from the early 1980s four-for-a-dollar (and score that sweet decade-old chewing gum!)]. At home, we’d pull out shoeboxes of cards and spend hours assembling our dream teams, trading back and forth to complete sets and build stockpiles of our favorite players.

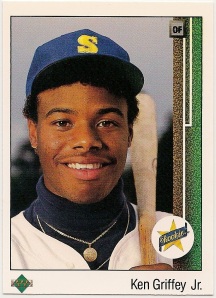

Mine was Ken Griffey Jr. If you were a collector in the 1990s, you understand. The Kid was destined to be the greatest player in the history of the game. As such, you could find Griffey posters, bats, baseball, Wheaties boxes, action figures, yo-yos… a kite (yes, I had them all). The prize of my collection – the 1989 Upper Deck rookie card. It was easily the most sought-after modern-day baseball card in my time. It’s value went as high as $120 (a Barry Bonds rookie card was going for $2). I put it in a plastic case so thick it could have stopped a bullet and proudly displayed it at the center of my card shelf.

Mine was Ken Griffey Jr. If you were a collector in the 1990s, you understand. The Kid was destined to be the greatest player in the history of the game. As such, you could find Griffey posters, bats, baseball, Wheaties boxes, action figures, yo-yos… a kite (yes, I had them all). The prize of my collection – the 1989 Upper Deck rookie card. It was easily the most sought-after modern-day baseball card in my time. It’s value went as high as $120 (a Barry Bonds rookie card was going for $2). I put it in a plastic case so thick it could have stopped a bullet and proudly displayed it at the center of my card shelf.

Griffey would have cruised past Hank Aaron’s career home run mark a few years ago, and done it cleanly. As steroid-enhanced hulks with enlarged heads and shrunken genitals took over the sport, Junior’s swing looked as pure as ever. From 1996-2000, Griffey compiled five straight 40+ home run, 100+ RBI seasons. But then came the injuries – a bevy of them. From 2001 to his retirement in 2010, Griffey had only three seasons in which he played more than 120 games. The streak he rode into the 21st century? He would never again achieve either mark.

As Griffey declined, so did my interest in collecting. It was not the causation, however. I had other favorite players – Greg Maddux, Cal Ripken, Chipper Jones to name a few. It just so happened that Griffey’s decline coincided with a dramatic shift in card collecting – one that killed the hobby for children to come.

Indeed, the CBS story came as no surprise to me. I already knew the truth: I was part of the last generation of childhood baseball card collectors.

No, it wasn’t the rise of the Internet, as the story claimed. Nor was it the rise of the NFL (did you know anyone who collected football cards?). It also wasn’t the insert-card mania that began with the Finest Refractors from Topps (the only baseball card maker left today). (In the mid 1990s, card makers would design cards of increasingly cool-looking color and gloss and place them in packs at rare odds. Quickly, they overdid it, flooding the market and making insert cards hardly the valuable rarity they once were.)

To the contrary, these were high times for the casual collector with shallow pockets. Cool stuff was out there, and it didn’t cost you a fortune to add it to your portfolio (or your plastic-sleeved 3-ring binder, more accurately).

To the contrary, these were high times for the casual collector with shallow pockets. Cool stuff was out there, and it didn’t cost you a fortune to add it to your portfolio (or your plastic-sleeved 3-ring binder, more accurately).

In 1997, Upper Deck upped the insert card ante, when they placed patches of game-worn jerseys on extremely rare cards (the 3-card set featured Griffey, Tony Gwynn, and – for some reason – Rey Ordonez). Again, the industry followed by chopping up all kinds of jerseys, bats, bases… even loading clumps of game-used dirt into a card. Then, they started purchasing and destroying vintage memorabilia from the likes of Babe Ruth, Mickey Mantle, and Ted Williams, to place slivers on cards. And while prices retreated from the values of those first three jersey cards, they remained well outside of the realm of the child/casual collector.

But there was still hope in the basics. For even a novice knows that in the world of collecting, nothing beats a good old-fashioned rookie card. Except for a professionally-graded mint Bowman Chrome autographed game-used baseball rookie card…

If there was any hope for kids to remain interested in the hobby, grading killed it. Professional grading services would certify the condition of your cards for a fee of $10-20 per card (or, a couple weeks allowance; or, 4-8 packs of new cards). Get a certified 10/10 mint rookie card back in the mail? That piece of cardboard just became gold (come back less than that, and you just wasted your money).

Grading sent valuations in the card industry soaring to ridiculous levels. That same 1989 Upper Deck Griffey rookie card graded a 10 ballooned ten-times in value from around $100 to around $1,000. In truth, it was even more dramatic than that, as the demand for premium graded cards made ungraded cards sharply decline in value.

Grading sent valuations in the card industry soaring to ridiculous levels. That same 1989 Upper Deck Griffey rookie card graded a 10 ballooned ten-times in value from around $100 to around $1,000. In truth, it was even more dramatic than that, as the demand for premium graded cards made ungraded cards sharply decline in value.

Between the game-used, autograph craze leading to packs of cards in excess of $100 (or $799; or $2,000) and grading making virtually any notable rookie card a triple-digit commodity, childhood collectors couldn’t play in the sandbox anymore.

It’s not that we were in it to make money; it was more about the “thrill of the chase” as some great friends of mine once said. But we were still collectors, and we were still aware of the monetary value of what we were doing. So, when it became obvious that our passion was worthless – indeed, losing money – without pouring significantly more cash into it, we bowed out in droves.

Now, there’s no one left, except for dealers trading amongst each other – the only people with the stomach to pour so much cash into a child’s game that the child can no longer afford to play.

A Ken Griffey Jr. poster still hangs in my bedroom. It is the lone piece of my childhood collection still on display. My cards are packed away, probably not worth the fortune I had imagined when I was younger. They were a great part of growing up – a nostalgia not unlike the game itself. One that was lost for a generation of youth by the greed of the few.

Dylan’s greatest pleasure in researching this piece was the discovery that, “Griffey Jr.” is still the first Google autocomplete suggestion for the name “Ken.” That is, until he discovered this, from a rapper named “Macklemore” (I can’t make this stuff up…)

“I don’t really collect cards anymore, just a box and some old cardboard

Memories embedded in the dust, in the fighters that age just like us livin’ some where off in the drawer”

I don’t even like baseball, but you write about it so passionately that I can’t help but get into it.

Dear Dylan;

I need some advice (don’t we all?).

I am 72 and need to sell my collection of Topps and Bowman cards from the late 40’s and early 50’s. Sadly, I need the cash to live on. There are 20-30 cards with big names, including a rookie Mantle, and another 200-300 cards of lesser known players. They are not in mint condition, but they are all in good condition. I bought them from the corner grocery store in Salina, Kansas during those years, and my mother was kind enough not to throw them out.

My question is, who can I trust to sell my cards for me? I do not feel competent to try to list them on ebay or elsewhere to sell them. After holding the cards for 60 plus years I am reluctant to turn them over to just anybody. I was hoping you might be able to recommend a reputable dealer? I live in the Atlanta area and my cards are in a safe deposit box in Santa Cruz, California. I could arrange to send the cards (heavily insured) to the right person who could market them for me.

I very much appreciate your taking the time to read this and pass me your advice.

Many thanks,

Paul Cummins

678-354-3880