“Fake news” defined an election, and continues to play a prominent role in the presidency of the candidate that most benefited from all of its forms. Gather a bunch of journalism educators together, and it’s no surprise we’re going to want to talk about it. That’s what happened in Chicago at the 2017 annual conference of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC). Continue reading “Trust in a fake news world”

Tag: Academia

Assimilation vs. Contrast: Making sense of the relationship between biased assimilation and hostile media perception

How do partisans arrive at seeing the world differently than the rest of us? I combed the research that’s been done, and look at where we need to go next.

This paper was presented May 27, 2017 at the International Communication Association Annual Conference in San Diego, Calif.

Political ideologues, religious zealots, die-hard sports fans… people who are heavily invested in a “side” tend to see the world differently than those who don’t have a dog in the fight. Over time, we’ve amassed a wealth of research that exhibits partisans entrench in their positions either by merging evidence into their argument that probably doesn’t belong (something called assimilation), or by dismissing any threatening information as irrelevant, biased, or hostile (contrast).

What’s less clear is how the partisan mind determines its method of biased information processing – how do we choose between assimilation or contrast?

The two have largely been studied in their own separate arenas, but it makes sense for us to come together. The connection has been there for a long time, dating back to the Sherifs’ work on social judgment, which suggested “latitudes” of acceptance or rejection of dissonant messages. More recently, Albert Gunther and colleagues suggested an assimilation-contrast continuum.

But how would that work? I examined the existing literature within two theoretical frameworks – biased assimilation and hostile media perception, to search for key predictors. Those can be grouped into two primary categories: Continue reading “Assimilation vs. Contrast: Making sense of the relationship between biased assimilation and hostile media perception”

Sunday morning talk shows and portrayals of public opinion during the 2012 presidential campaign

The 2016 presidential campaign has been unique thus far, to say the least. It makes the 2012 cycle look downright boring. Yet, one aspect of the 2012 campaign that stood out to me was the use of public opinion polling by media to frame the race.

This paper was presented August 7, 2016 at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Annual Conference in Minneapolis, Minn. An early version was presented February 27, 2016 at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Midwinter Conference in Norman, Okla.

The 2016 presidential campaign has been unique thus far, to say the least. It makes the 2012 cycle look downright boring. Yet, one aspect of the 2012 campaign that stood out to me was the use of public opinion polling by media to frame the race. Leading up to Election Day, it seemed pretty clear that President Obama would have the electoral votes to win a second term. Election forecasting guru Nate Silver thought so, and most polling data agreed.

However, a completely different picture was painted in conservative media – at least in a few anecdotal instances. Fox News contributor Dick Morris infamously predicted a “landslide” victory for Mitt Romney, while Karl Rove’s refusal to accept Obama’s victory-sealing win in Ohio made for awkward Election Night coverage for the cable news ratings leader. Both had evidence on their side – poll numbers that made it look like Romney was indeed going to win Ohio and the White House. But those polls were in the minority, and they were wrong.

This matters. Previous research suggests that publishing of public opinion polls can actually influence public opinion, and eventually, voting. To be fair, these findings have always been tough to untangle. Does a poll showing a candidate with a big lead create a bandwagon effect where everyone wants to vote for the inevitable winner, or does it spur an underdog effect in which the losing candidate’s supporters mobilize to close the gap? Does depicting a close race boost turnout, while voters skip out on a projected blowout? There’s evidence of all of these. Continue reading “Sunday morning talk shows and portrayals of public opinion during the 2012 presidential campaign”

Involvement Types and Hostile Media Perception: A Consideration of Campus News

Presented March 27, 2015 at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Southeast Colloquium, Knoxville, Tenn., Newspaper and Online News Division.

Presented March 27, 2015 at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Southeast Colloquium, Knoxville, Tenn., Newspaper and Online News Division.

Information about accessing this paper and associated materials available here, or by visiting the Academia page on dylanmclemore.com.

Hostile media perception (HMP) is a fascinating occurrence. Have two people highly invested in different sides of a divisive issue read the same newspaper article, or watch the same interview, and they will each declare emphatically the exact same message to be hostile toward their side of the argument. We’ve documented this for decades; what we struggle to explain is exactly why it occurs, which makes it difficult to correct for the bias.

This paper – part of a larger study – examines one possible explanation that could equip journalists and other message creators with a way to conquer HMP. We’ve long suggested that higher levels of involvement lead to more careful, and therefore more accurate message processing. The problem for partisans is that when your mind is full of arguments defending your position, thinking about a new argument more carefully probably isn’t going to result in objective reasoning.

Another way of looking at involvement is not in its extremity, but rather its type. Following Johnson and Eagly’s conceptualizations (1989, 1990), this study looked at how value, outcome, and impression involvement related to HMP. Briefly, value involvement refers to deeply held convictions, beliefs, and… well… values. The principles that guide your life. Those contribute to and are shaped by partisanship. They’re also pretty important things to defend, thus likely predictive of HMP. Outcome involvement is triggered when you recognize tangible consequences associated with a message. It would seem to be a deterrent to HMP. You may hate the IRS and everything they stand for, but if news breaks about a change to the tax code that could get you a big refund (or hit you with a huge hike), you might put aside your feelings and try to figure out the particulars. Impression involvement has more to do with fitting in socially, with a tendency to be weaker and more normative than the other involvement types. The assumption is that it won’t affect HMP, but that’s never been tested empirically.

So, an experiment was conducted. Participants – students on a college campus that had just experienced bouts of fraternity and sorority misconduct – read fictitious newspaper articles about disciplinary sanctions being taken against the Greek organizations. This context produced strong partisans on both sides of the issue. And, the more extreme one’s opinion about whether the sanctions were a good idea, the greater the perception that the newspaper article was taking the exact opposite stance – classic HMP.

The involvement types, however, didn’t behave as anticipated. Value involvement predicted increased HMP among those opposed to sanctions, but was overshadowed by the strong influence of outcome involvement. Instead of counteracting perceptual biases, high outcome involvement only served to heighten HMP. For supporters of the sanctions, value involvement actually served as a weak resistance to HMP. About the only clear and expected result was the lack of a relationship between impression involvement and HMP.

Digging deeper into the data, it looked like the strange findings regarding involvement types might have been the result of quick, heuristic defense mechanisms on the part of pro-Greek participants. While supporters of sanctions perceived differences in various article versions fairly accurately, those opposing sanctions saw less nuance and almost uniform bias. This researcher has an idea as to what might have been the catalyst for that information processing shortcut, and explores it in the second phase of this study… coming soon. (Well, soon-ish… he has to finish his dissertation first.)

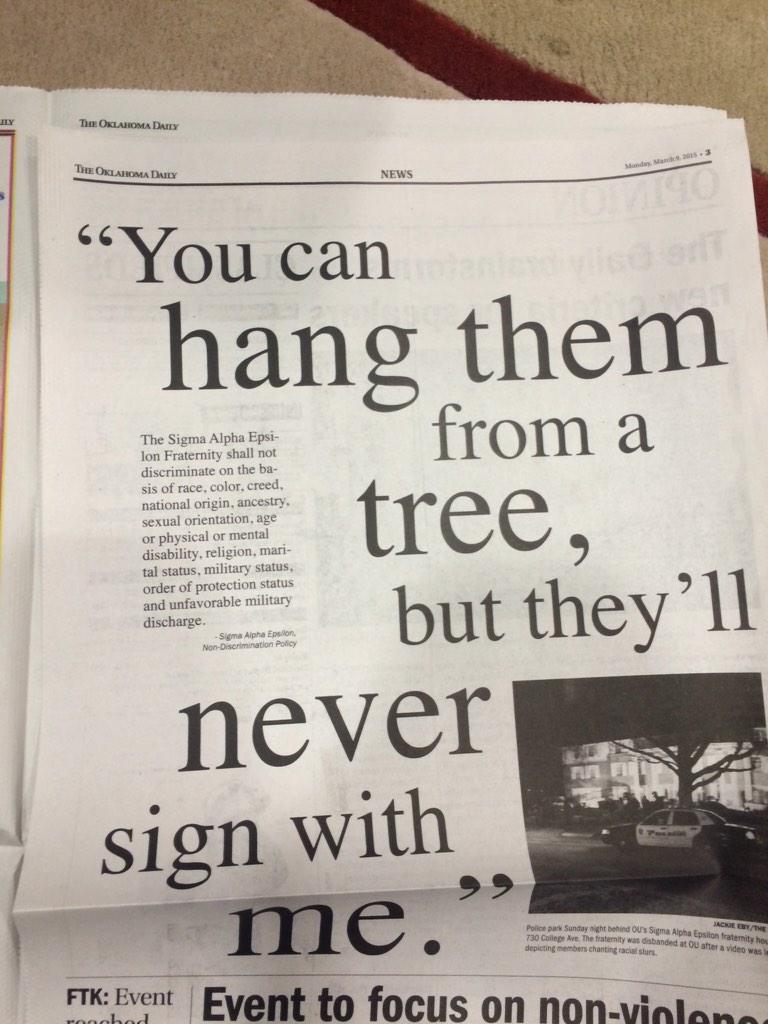

Reviling racism and protecting free speech: PR, education, and the First Amendment in Oklahoma’s SAE controversy

There will never be a n*gger at SAE

There will never be a n*gger at SAE

You can hang him from a tree

But he’ll never sign with me

There will never be a n*gger at SAE

Some ignorant frat guys from the University of Oklahoma sang this on a bus. It was filmed and shared online. Within 24 hours, the university severed ties with the fraternity and shut down their campus house. Within 36 hours, two students appearing to lead the song had been expelled.

They deserve it. The existence of this line of thinking, much less the existence of a welcoming audience for such a message, makes me angry.

They deserve it. But they cannot be expelled, because it runs counter to the purpose of institutions of higher education and foundational American beliefs about expression.